A Recollection of My Father’s Garden

Outside the window of the room where my mother read me to sleep every night until she could no longer climb the stairs, my father’s garden slowly churns and heaves with the seasons, sinking into that quiet beauty that in some measure possesses all decrepit things. In winter months, the decay seems especially pronounced. Along the trusses of rusted wrought-iron archways, the brittle remnants of trumpet vines and clematis cling to their posts, even into the heavy snows of January and February. Come Spring, the earth will give rise to new shoots which in their inexorable, programmed ascendance will tangle with their desiccated predecessors, and in the way that all things must, the living will inhabit the husks of the dead. After the sterile air of winter warms, the perfume of those orange and purple blooms will return with a confused assortment of murmuring insects lusting after the commingling scents. On cement walkways beneath the snow, moldering piles of vegetable matter will persist into the early days of summer, the detrital marks of my father’s abandoned attempts to maintain a space which formerly flourished under the care and direction of his meticulous hand. The creaking, mechanical groan of a water pump will suffuse the yard until the sun’s rays liberate a little ice-swollen pond from its present suspension; then, one might catch the tiny golden flashes of fish scales in the undulating, refracted light of the pool as my father, having tired of the water pump’s audible, if spiritless complaints, rakes algae from the surface in stinking wads and piles it noisily on the sidewalk.

During the summer that I turned fifteen, my parents set about the construction of the garden as a sort of means to answer the increasing limitations imposed by my mother’s illness. Her disease having progressed to a point which rendered travel impracticable, they conceded this loss and determined themselves to realize a certain internal vision of loveliness—my mother’s—and transform the backyard of our home into a kind of manicured paradise, an English garden on the plains of Colorado. My father produced the greatest share of labor in the manufacture of my mother’s dream, carrying out all the work for which he possessed the requisite skill and machinery. Being fifteen, I helped him only when compelled by argument or guilt, and spent the greater share of that summer’s hours in the shade of the basement, playing my guitar badly over the hum of engines—tillers, tractors, and the occasionally rented wood-chipper. I would not recognize for many years the profound depth of what must have been a sometimes grudging devotion contained in that small miracle which my father had almost single-handedly wrought in our yard.

For a time, the flora of the world congregated harmoniously in the space. For what were to my mother two of the summer’s most anticipated weeks, a pink hibiscus near the pond exploded with dozens of its splendid, short-lived blossoms, the enormous petals of which retained a kind of hushed comeliness even as they scattered, wrinkled, and dried on the concrete below. Irises of every conceivable shade—the particular favorites of my mother—lit the walkways with their exuberant, doggish faces and saturated the months of May and June with a pleasant aroma. The trumpet vines and clematis climbed the yard’s wrought-iron arches less wildly than they are now permitted and in their bloom adorned the elegant, petaled portals through which my mother piloted her orange wheelchair. As the years passed and I slowly returned from the largely invented gloom and self-obsession of my teenage years, I would trail along behind her through the snaking concrete paths which simultaneously ensnared and exposed the plant-life of the space, listening as she identified a patch of weeds to be pulled or a half-dead tree branch to be pruned. She had a habit of remarking on the relative poor health of the aspen trees in a climate for which they were well suited, what seemed to her a strange, perhaps even mystical irony of the garden’s fecundity. I don’t believe I ever came to appreciate the garden in the way my mother had. Where she found beauty in order and improvement, I later came to recognize the neglected value of degeneration and the sad rapture of it; I often sighed and drank in the stillness of it all as I read, according to habit, at the garden’s fringes on an old iron swing.

I might have read into my experience at that time a parallel between my life and the garden itself. I might have remarked on the continuity between my mother’s decline and the slow regression of the yard into a state of wilderness. I didn’t. As my father’s time was increasingly demanded by the realities of care giving and the garden began its slow descent into rot, I might have seen my father’s entire estate in the melancholic hues of Wuthering Heights—my family and I the fallen aristocratic denizens of a once great English manor. I might have viewed the slow deterioration and the onsetting putrescence of the garden in terms of Baudelaire’s Paris of the Second Empire; I might have felt in it the dull weight of some vague, unknowable future apocalypse, the inevitable and total end of civilization as brought about by that dubious collection of forces we once called progress. In the months following my mother’s death, I might have seen in my father the crotchety, eccentric shopkeeper of Dickens' Bleak House, ready at any second to spontaneously combust amid piles of junk and mechanical detritus which he amassed for whatever cryptic psychological reasons he ultimately did. These ghosts of the nineteenth century haunted my father’s garden then as they do now, but suffering is so rarely the crucible we imagine it to be when we are young.

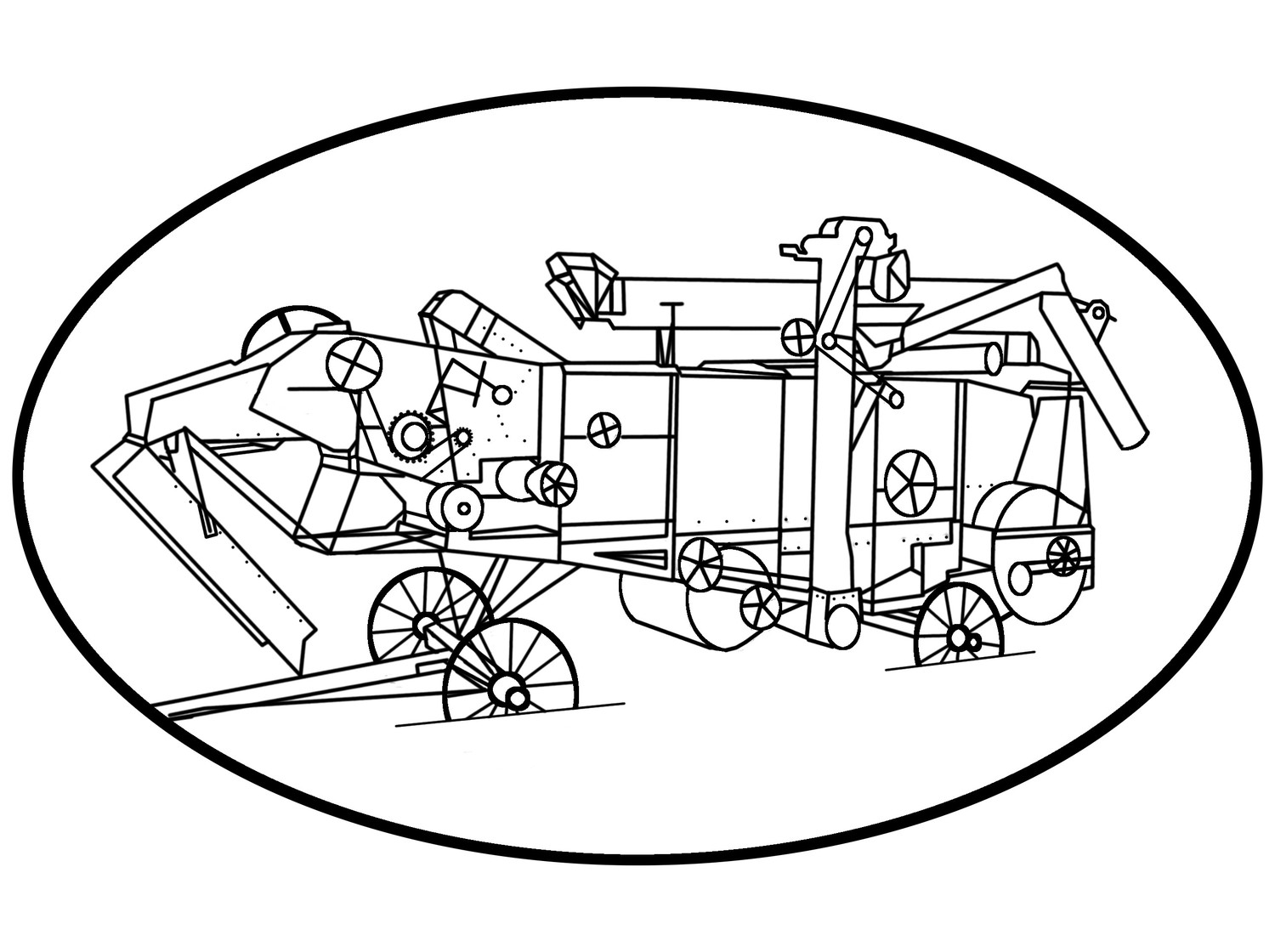

As for my father and his house, they persisted in those months in a state of unqualified disarray. Both were marked by an ostensibly absolute movement from exterior to interior. Inside his home, strewn across every imaginable surface lay the disarranged components of various machines in equally various stages of incompletion, some which once functioned wholly or partially before their hasty, often capricious disassembly and others which functioned only in my father’s disordered dreams, the half-drawn visions of a future ruled by the ruthless regulation and efficiency of his engines, instruments, and apparatuses. Gradually, some of these components were assembled and reanimated or bestowed with new life entirely, retrieved from their languishment in the electronic graveyard of my father’s home. Their defective and dismantled comrades still sulk and await my father’s unpredictable whims, always charged with the potential for resurrection. In the end, I found these cycles of collection and accretion, of disjunction and assembly utterly baffling and, unable to connect more meaningfully with his eccentricities, abandoned my father to the cluttered chambers of his home and thus to his little, mostly harmless madness.

Nevertheless, I saw my father often at that time, but for my part, mother’s death had altered me in an elementally different way—imbued me, perhaps, with a new sense of symbolism. I no longer take the opportunity to read in my father’s garden when I visit. In a migration toward interiors which in some ways parallels his, I now prefer to sit indoors. Just outside the room where my mother read me to sleep every night until she could no longer climb the stairs, an orange wheelchair sits in the same corner it has sat since the day my father and his brother carried it back from the hospital. I ask after it each time I’m home. “Surely it could do someone some good,” I say. “Oh, the motor’s shot,” or “the battery’ll have gone bad by now,” or “such and such part wants replacing on the circuit board,” my father invariably replies. “You can’t donate ‘em in that condition.” And so, resigned to leave the chair as a kind of somber, if curiously fitting monument in the cemetery of disused machines, I’ll rummage through a box of his old books and pull out something by Bradbury or Clarke or Asimov and retire to that room beside the wheelchair, a space that strangely is and is no longer mine. I’ll leave the garden to its ruin, lay down on my childhood bed, and retreat into one of those fantastic future worlds in which mankind, instead of having destroyed itself or perished in some unforeseen cosmic cataclysm, has peopled the stars and seeks, as I do each time I look up through the threshold of my room at my mother’s chair, to find new ways to live with empty space.