Thousand-Year Storm, County Landfill

When the floodwaters withdrew and carried

bloodwarmth in their tow to dissolution,

the county, still soused to its foundations,

gathered carcasses at the canyon’s mouth—

the drowned, twelve dollars every hundred pounds

to cull the bedraggled dead and heap them

at the dump. Ponderous animal mass:

catalogued, weighed, each drear, exhausted lump

labeled, clean in the bureaucratic tongue—

putrescible waste. Thus disposed, the mound ached,

swelled, and bent slack, waited for a god

to pity its aching.

Heaped portentously, bridge beams and concrete

(sudden megalithic trash), storm-splintered

trees, homes—together wove a great gnarled arch;

the flood’s destruction yawned like doorways

of a dead temple whose dark, ruined mouth

once housed holy phonemes.

Gulls’ bright orbits, like prayers, trace contours

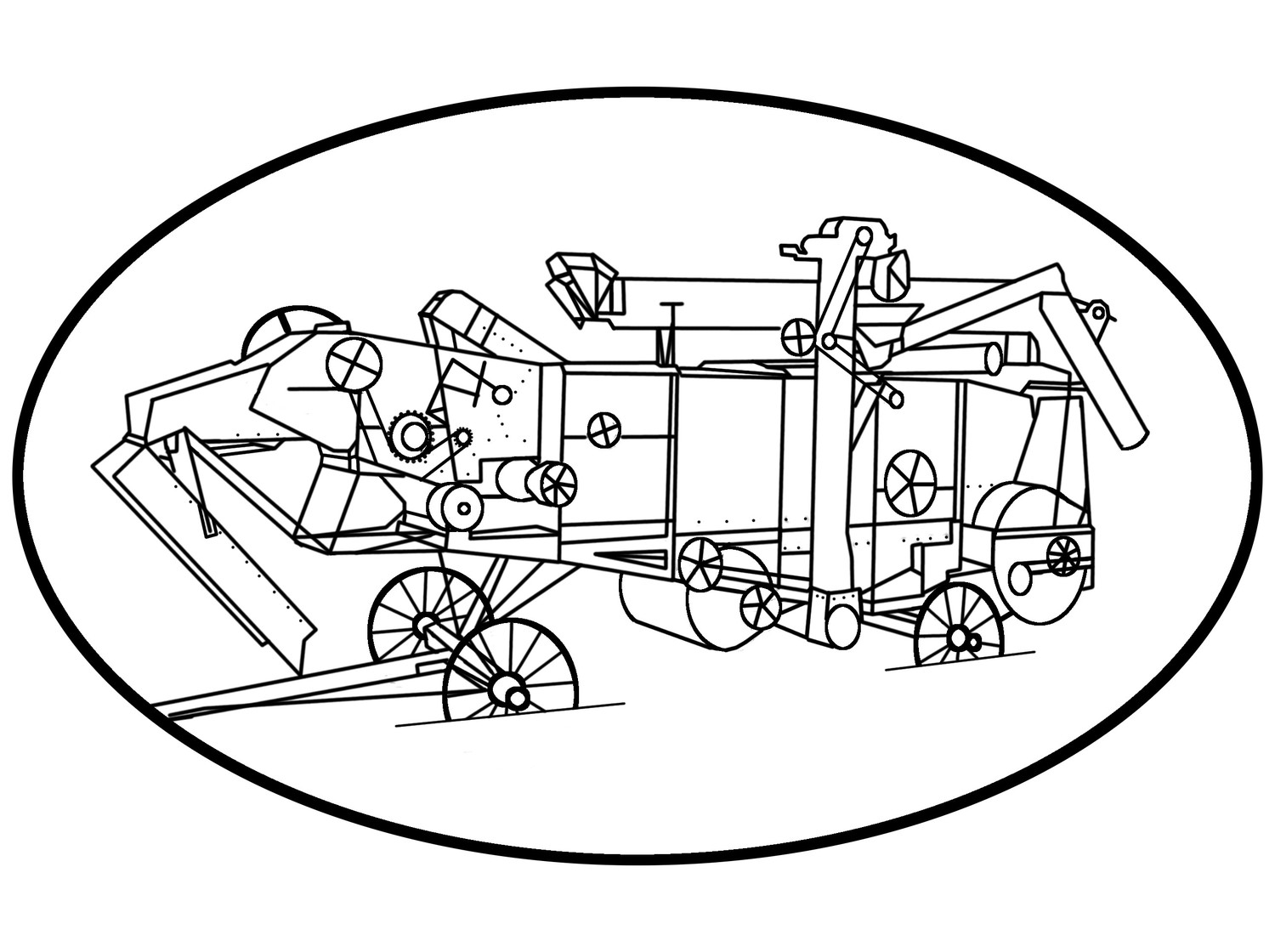

above the heaps where tractors range and rake

the ragged iron of their teeth, marshal

thunderheads of diesel smoke, and growl

through steel slats—leak the deep guttural boil

of fire-churning vitals.

Now, down-mound, appliances cluster—

herds: the fauna of an approaching world,

some dark planet hung far off in ether

like the counter-earth of Philolaus.

Rusted bulks congregate, weather the nights

under speechless stars, cold, waiting an end:

the scrupulous turn of a hand to loose,

to bleed Freon, disassemble, and ship

each discrete piece toward resurrection.

Machine hearts hiss; coils of refrigerant

gasp, weep through their ruptured copper piping.

Darkly, you listen.

Yet,

the stars persist in their troubling muteness;

of these white beams, how many mark suns that

died their distant deaths in distant epochs?

If, of all the host of heaven, one still lives,

who can know which one it is?

(Pacific Review, 2018)